Hidden Speakeasies of the North: Prohibition’s Secret Scene in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Bismarck

By the glow of a single bulb in a smoky cellar, a tap pours an illicit brew into clinking glasses. Overhead, the streets of Fargo lie quiet under midnight frost while underground tunnels echo with the whispers of bootleggers.

Prohibition in North Dakota wasn’t just a footnote – it was a full-blown saga of hidden speakeasies, enterprising bootleggers, and even an unlikely connection to Al Capone. In Fargo, Grand Forks, and Bismarck, creative minds found ways to keep the liquor flowing under the nose of the law. And interestingly, the beer brewed (or not brewed) during those dry years still casts a shadow on what we drink today. Let’s journey back to the 1920s and 30s, when temperance laws turned ordinary folks into outlaws, and explore how that wild era influences the craft beer in your glass.

Main Street in Minot, North Dakota during the Prohibition era, nicknamed “Little Chicago” for its bootlegging activity. Minot’s experience echoes the hidden scenes in Fargo, Grand Forks, and Bismarck.

“Dry” North Dakota and the Rise of Speakeasies

North Dakota entered the Union bone-dry in 1889 – written into the state constitution was an outright ban on alcohol. Saloons from Fargo to Bismarck were ordered shut by July 1, 1890. This bold experiment predated national Prohibition by three decades. Of course, making alcohol illegal didn’t make the desire for it disappear. It only drove drinking underground and, sometimes, across state lines.

In those early “dry” days, Fargo’s drinkers found a convenient loophole: the Red River. Just across the water in Minnesota stood the city of Moorhead, which remained “wet” and full of saloons. Enterprising bar owners in Moorhead set up “jag wagons,” large horse-drawn wagons providing free rides to shuttle thirsty Fargo patrons over the bridge for a legal drink. By night, these wagons clattered back and forth, carrying Fargo residents to Moorhead’s lively bars and back home again. The arrangement lasted until Moorhead (and the surrounding Clay County) went dry in 1915, closing that boozy escape hatch just ahead of nationwide Prohibition.

When federal Prohibition hit in 1920, the entire nation had to adapt to the dry laws North Dakotans already knew too well. Across the state – Fargo, Grand Forks, Bismarck, and beyond – saloons shuttered or reinvented themselves as “soft drink parlors.” But behind many a soda counter or café front, a secret liquor trade continued. Hidden rooms, false walls, and password-protected doors became standard fixtures as speakeasies took root. In Fargo, the more rough-and-tumble hidden taverns earned the nickname “blind pigs.” Patrons would pay to see a supposed attraction (say, an animal on display) and in return receive a complimentary cup of booze in a teacup. It was a flimsy ruse, but it satisfied the letter of the law – and kept the hooch flowing.

Bootlegging Tricks and Tunnels

Supplying these secret bars was a dangerous game of cat-and-mouse with law enforcement. Bootleggers developed ingenious tricks to smuggle alcohol and avoid arrest. One popular tactic across North Dakota was the signal light system: rural sympathizers would leave lamps burning in farmhouse windows along known liquor routes whenever police were nearby. If a bootlegger driving a back road saw a light in the window upstairs, it was a silent warning to turn around and take a different path. These warning lights were so effective from Minot down to the South Dakota border that the supply of illegal whiskey at one point surged and actually drove prices down, a rare win for consumers during Prohibition.

Smugglers also turned to the earth itself for cover. In several North Dakota cities, underground tunnels became arteries of the bootleg booze network. Minot, in the north-central part of the state, became especially infamous for its tunnel system – so much so that it earned the nickname “Little Chicago.” According to local legend, none other than Al Capone ran an elaborate liquor smuggling operation in Minot, using hand-dug tunnels that snaked beneath the city. When a devastating flood hit Minot in 2011, homeowners rebuilding their basements stumbled upon hidden rooms stocked with old moonshine and tunnels leading off toward the river. These long-forgotten passageways once allowed bootleggers to whisk whiskey barrels under the streets, unseen by the cops above.

Minot wasn’t alone. Throughout the state, secret corridors allegedly connected breweries, warehouses, and speakeasies. In Fargo, rumors abounded of tunnels linking downtown basements – possibly old service tunnels repurposed for stealthy booze runs. While some of Fargo’s tunnel tales are hard to verify (and some may have been heating tunnels or fallout shelters later exaggerated into legend), the city’s proximity to both Canada and wet Minnesota made it a key juncture for smuggling. Farther west in Bismarck, locals whispered about a tunnel running from the opulent Patterson Hotel to the train depot across Main Street. Why a tunnel? Perhaps to discreetly roll in barrels of Canadian whisky shipped by rail, or to give high-profile guests a secret escape route during a raid. The Patterson Hotel’s management never confirmed the tunnel’s existence (the idea remains a rumor), but they didn’t shy away from covert activity. The hotel became Bismarck’s most notorious speakeasy, with an elaborate alarm system installed to warn of approaching law officers. Patrons could merrily enjoy their “tea” in fine crystal goblets, confident that a lookout would ring a bell or flash a light if any uninvited revenuers neared the door.

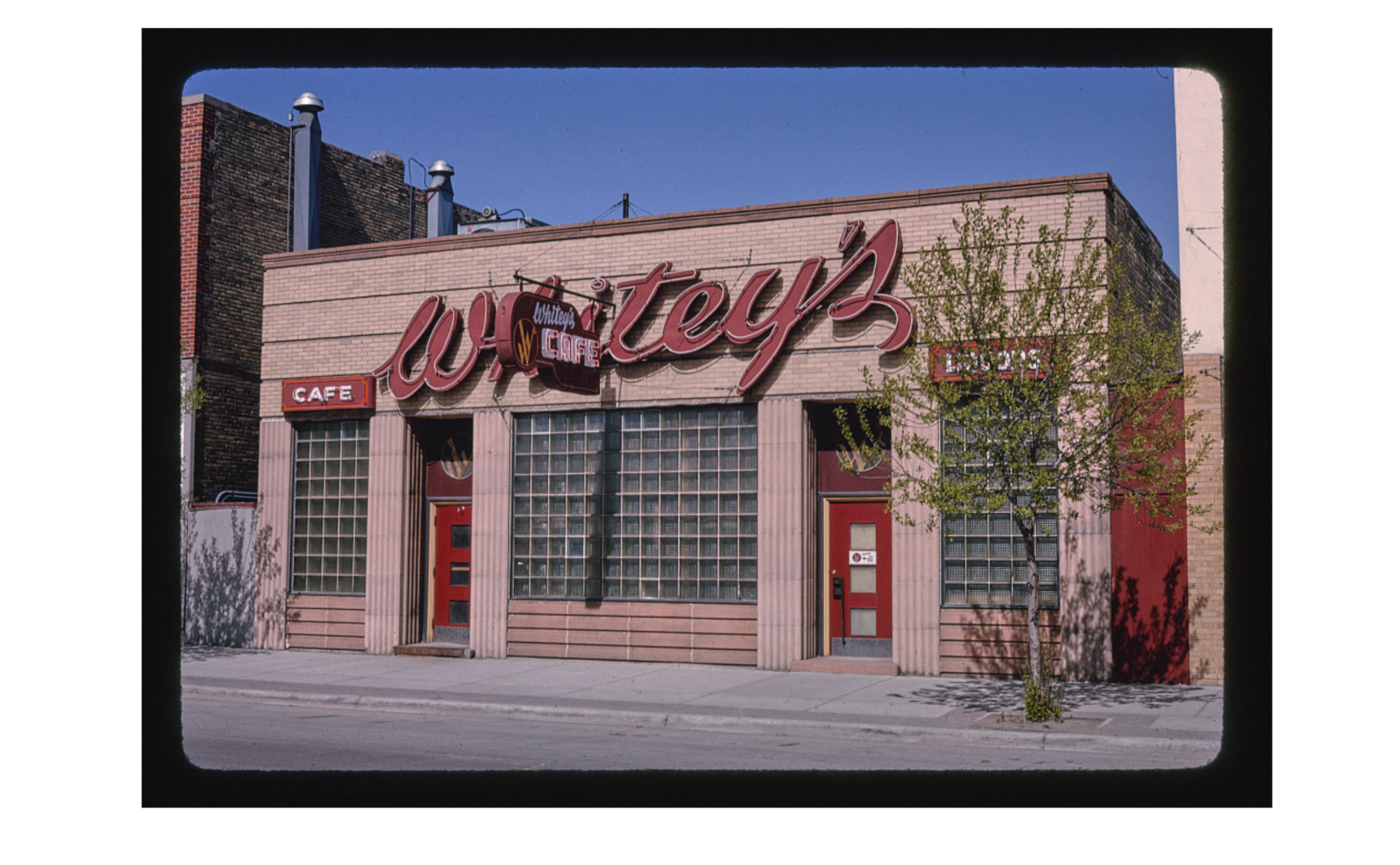

Meanwhile, Grand Forks had its own unique scene – which often actually took place across the river in East Grand Forks, Minnesota. When North Dakota went dry in 1890, many Grand Forks saloon keepers simply moved their businesses to the Minnesota side in East Grand Forks. By the 1900s, East Grand Forks’ DeMers Avenue was a neon-lit oasis of indulgence, crammed with saloons and dance halls. Even after Minnesota turned dry in 1915, East Grand Forks didn’t give up its wet ways – it just pushed them underground. During Prohibition, East Grand Forks blossomed with speakeasies and gambling dens. Slot machines whirred, jazz bands played, and moonshine flowed freely in back rooms. Locals wryly dubbed the town “Little Chicago” for the reputed influence of Chicago mobsters like Capone in supplying the liquor. Indeed, local legend holds that Al Capone’s syndicate supplied much of the Canadian whisky pouring into East Grand Forks speakeasies. The city police, perhaps recognizing the economic lifeblood this under-the-table trade provided, typically staged only a token raid or two each year. Bar owners would pay a small fine in court and promptly return to business as usual. One popular speakeasy, Whitey’s Wonderbar, even installed the nation’s first stainless-steel horseshoe bar counter in 1930 to class up its joint – a feature so unique it was featured in Time magazine in 1939. (That very bar counter survives today in East Grand Forks, a tangible relic of the era.)

In Fargo and Grand Forks alike, news of the day was filled with reports of bootlegger busts and liquor seizures. In one Fargo case, authorities confiscated 640 gallons of pure alcohol labeled as “hair tonic” in a railroad depot shipment – enough hair tonic to coiffure an army, but more likely destined for speakeasy cocktail glasses. In another instance, an entire pipeline was discovered running underground from the courthouse in Minot to a downtown hotel; when judges poured out seized liquor down the drain as required by law, enterprising crooks had simply rerouted the pipes so the booze would flow straight to the hotel bar taps. This was the creativity of Prohibition-era criminals: if life gives you lemons, build a pipeline and make spiked lemonade!

Al Capone’s Surprising Ties to North Dakota

No story of bootlegging in the northern plains would be complete without Chicago’s infamous mob boss making a cameo. Al Capone never openly set foot in North Dakota (to our knowledge), but his presence was felt in the shadows. As mentioned, both Minot and East Grand Forks earned the moniker “Little Chicago,” suggesting Capone’s bootlegging network reached into those communities. Canadian whisky – the good stuff, like Seagram’s – was a prime import for Midwestern bootleggers, and much of it filtered through Capone’s distribution channels in Winnipeg and Ontario before slipping across the border into North Dakota. From there, local gangs took over, hauling liquor by car, truck, or rail to city speakeasies. It was a lucrative, multi-layered operation, and Capone, ever the businessman, was happy to have customers in Fargo and Grand Forks willing to pay for his product.

In a twist stranger than fiction, one of the people fighting that flow of illegal liquor was Al Capone’s own brother. James Vincenzo Capone, the eldest Capone brother, had left the family in Brooklyn years before and reinvented himself in the West as Richard “Two Gun” Hart. By the 1920s, James Capone was working as a Prohibition agent in North Dakota, raiding stills and arresting bootleggers on the Standing Rock Reservation and beyond. A State Historical Society photograph from 1926 shows him posing in Fort Yates, ND, armed with a rifle and surrounded by confiscated jugs of moonshine – a lawman Capone in a land where the Capone name was simultaneously infamous for supplying hooch. One can only imagine the awkward family conversations had the brothers ever crossed paths at a hidden Fargo bar versus a police station!

Capone’s indirect presence lent an extra dose of drama to North Dakota’s bootlegging scene. Stories still circulate of his men hiding out in small North Dakota towns, or big-city gangsters sending trucks laden with beer down lonely prairie highways. Whether embellished or true, these tales cement the idea that the Peace Garden State had a small supporting role in the nationwide bootlegger empire that made Al Capone a multimillionaire. In East Grand Forks, for instance, there were so many high-end clubs with slot machines and jazz that a visitor might have felt closer to Chicago’s South Side than a small Midwestern town.

Bismarck’s Patterson Hotel: Glamour and Secrecy

While Fargo and Grand Forks had plenty of low-profile blind pigs and rural runners, the city of Bismarck offered a more refined – yet equally illicit – experience during Prohibition. The crown jewel was the Patterson Hotel, a luxurious 10-story hotel that opened in 1911 and soon became the place for politicians and power brokers to gather. During Prohibition, the Patterson’s management didn’t let the law stop their hospitality. They secretly served alcohol in back rooms and suites, ensuring that legislators and lobbyists could still clink glasses after a long day at the State Capitol. The hotel had a sophisticated alarm system to protect its high-profile patrons – if an unknown or unwelcome guest (like a federal agent) approached, staff could trigger alerts to sweep booze off the tables and make the scene appear innocently dry.

The rumored tunnel linking the Patterson Hotel to the Northern Pacific Railroad depot across the street is part of Bismarck lore. Prohibition-era gossip suggested that expensive liquor traveled from train to hotel safe from public view. True or not, the Patterson’s willingness to bend the rules was very real. The bar in its Peacock Alley grill room became an open secret; even with shades drawn, the laughter and clink of contraband cocktails leaked out. Bismarck’s police, perhaps under political pressure, took a relatively light touch in raiding such elite establishments. Like East Grand Forks, the city occasionally made a public show of enforcement – a raid here, an arrest there – but in general, the speakeasy culture was tacitly tolerated in the service of keeping the social and economic peace. After all, many of Bismarck’s civic leaders were the very patrons sipping whiskey at the Patterson.

Prohibition finally died in 1933, and North Dakota (along with Minnesota) repealed its dry laws. The speakeasies unlocked their doors, legally this time, and places like Whitey’s Wonderbar and the Patterson Hotel’s bar continued on as legitimate businesses. Yet the legacy of those hidden gin-joints did not disappear – it survived in stories passed down, in physical artifacts like tunnels and bars, and, intriguingly, in the evolution of American beer itself.

From “Near Beer” to Craft Beer: Lasting Influence on Brewing

Prohibition didn’t just change how Americans drank; it changed what Americans drank. Before the dry era, German-style lagers and a variety of local beer styles (wheat beers, dark ales, etc.) were common. During Prohibition, however, most legal “breweries” switched to making “near beer” – malt beverages with less than 0.5% alcohol – or other products like soda pop and malt syrup. The real stuff was produced illicitly in backwoods stills or by bootleggers who weren’t exactly following Bavarian beer purity laws. Quality suffered, and many Americans either lost their taste for beer or turned to spirits and cocktails (which were easier to smuggle). An entire generation grew up with no memory of richly flavored beers; by the time drinking was legal again, palates had shifted toward milder flavors. As one beer historian noted, a generation raised on soda pop “rejected the bitterness of the Bavarian-style beers that had been popular in America before Prohibition and demanded something sweeter”.

The result was that after 1933, the surviving breweries (only 164 out of nearly 1,400 pre-Prohibition breweries reopened) catered to this new taste. They produced lighter, less hoppy beers – the ancestors of today’s mass-market American lagers. The robust pre-Prohibition lager, with its all-malt or malt-and-corn grist and assertive hop bite, largely vanished as a commercial style. Also gone were regional specialties like the Kentucky Common (a dark cream ale popular around Louisville) and countless local brews. American beer became nearly uniform and, frankly, a bit bland for several decades. This persisted until the craft beer movement many decades later revived the full spectrum of flavors.

However, the story has a happy twist. Today’s craft brewers, ever the experimenters, looked to the past for inspiration and rediscovered those lost styles. Historical research unearthed old brewing logs and recipes from before and during Prohibition, and brewers began reviving them. For example, the Brewers Association’s style guidelines now include “Pre-Prohibition Lager” as a recognized historical beer type – a pale, hoppy lager made with 6-row barley and flaked corn, just like early 1900s American brewers made before the taps went dry. Several craft breweries have tried their hand at this recipe, finding that drinkers enjoy the crisp yet flavorful profile. (Live Oak Brewing’s “Pre-War Pils” in Texas and Schell’s Brewery’s classic Deer Brand Lager in Minnesota are two examples – Schell’s has actually brewed Deer Brand since the 1800s and kept it alive through Prohibition and beyond.) Many craft brewers also produce cream ales – a style that survived Prohibition in a limited form – as a nod to America’s brewing heritage. And the once-forgotten Kentucky Common ale has been resurrected by historical beer enthusiasts who want to taste a bit of pre-1920s.

In a broader sense, Prohibition’s influence set the stage for the craft beer renaissance. With the post-Repeal beer landscape so homogenous, the door was open for people to crave variety. When homebrewing was legalized in 1979, hobbyists immediately started tinkering with recipes, exploring everything from hoppy India Pale Ales to rich stouts – beers bursting with character that their parents and grandparents never knew. As one account observed, only after the late 1970s did America “once again know an interesting variety of beer styles and tastes”. In a way, every craft beer brewed today is a reaction against the constrained beer culture that Prohibition inadvertently created. Had the 18th Amendment never passed, American beer might have evolved very differently. Instead, we had a 50-year pause on diversity – a pause that craft brewers have been making up for with gusto.

Legacy of the “Noble Experiment” in North Dakota

Back in the hidden bars of Fargo, Grand Forks, and Bismarck, if you had whispered to a bespectacled bootlegger that one day people would openly tour craft breweries and relish recipes from the Prohibition era, he’d probably chuckle and slide you another drink. Yet here we are. The underground tunnels have mostly been sealed or forgotten, but their stories captivate us. In Fargo today, you might find a trendy bar with a faux-secret entrance paying homage to the speakeasies of old. In Bismarck, you can dine at the Peacock Alley Grill, located in the very lobby of the old Patterson Hotel, imagining the clinking glasses and hushed toasts that once echoed there. In East Grand Forks, you can actually lean on Whitey’s original horseshoe bar rail – now lovingly preserved – and order a legal pint.

North Dakota, once the pioneer of Prohibition, now boasts a hearty drinking culture; by some counts it leads the nation in number of bars per capita. And its craft beer scene is blossoming, with breweries experimenting with local ingredients and even resurrecting historic styles. It’s ironic and wonderful: the state that tried to ban alcohol outright is now a place where beer history buffs can rejoice.

The hidden speakeasies and bootlegger trails of the 1920s have become a rich part of local folklore. They remind us that even a Constitutional amendment couldn’t quite tamp down the human impulse for a good time and a good drink. The resourcefulness shown – from secret tunnels and code signals to disguised “hair tonic” shipments – speaks to the ingenuity (and stubbornness) of North Dakotans. And the echoes of that time live on in the beers we enjoy. Next time you savor a pre-Prohibition style lager or even just a cold light beer, raise a glass to those Roaring Twenties rebels. Their fight for the right to imbibe shaped the course of American beer. In the end, the “Noble Experiment” of Prohibition failed, but it left behind a legacy of colorful stories and a beer scene that’s arguably more vibrant than ever – above ground and out in the open, where we can all cheers to history.

Cheers to the secret past that’s brewed the present.

Sources:

- Fargo History Project – Bootlegging: Historical overview of ND Prohibition, blind pigs, and smuggling tactics.

- Sabrina Hornung, Traveling Midwestern – “Bootleggers and Rum Runners” (Minot’s “Little Chicago” tunnels and statewide smuggling lore).

- Prairie Public Dakota Datebook – Capone and East Grand Forks: Details on East Grand Forks speakeasies, Capone’s rumored involvement, and the city’s “Little Chicago” era.

- State Historical Society of ND – A Capone in North Dakota: Story of James “Two Gun” Hart (James Capone) as a Prohibition agent in ND, with photograph of confiscated stills.

- Bismarck Café (history blog) – Dawn of a New Century: Info on Bismarck’s Patterson Hotel serving alcohol during Prohibition and rumored tunnel to train depot.

- CraftBeer.com – 12 Craft Beers That Taste Like Beer: Notes on pre-Prohibition lager style and its use of corn, exemplified by Schell’s Deer Brand.

- Craft Beer & Brewing Magazine – Prohibition: Analysis of how Prohibition shaped American beer preferences (sweeter, lighter beer dominating post-1933).

- Brülosophy – Pre-Prohibition Lager: Background on the style and its characteristics as a distinctly American beer that faded after 1920